- Home

- Suzy Parish

Flowers from Afghanistan Page 7

Flowers from Afghanistan Read online

Page 7

“OK, come on in, but you owe me. And don’t try and pay with that junk your wife sends.” I opened the door.

Travis barreled in.

Thorstad and his gang of munchkins popped into my head. “Do you know where I can get hold of Thorstad?”

“Who?” Travis mumbled through a mouthful of crumbs.

“Thorstad. I want to give him some of this candy to hand out to the kids.”

Travis swallowed. “He hangs out at the barbershop a lot.”

I grabbed the bag of pops, but not before removing a grape one and laying it on my desk. I headed out the door and down the hallway.

“You want me to come with you?” Travis called after me.

“No, stay here. Watch Phoenix.”

~*~

I pushed the door to the barbershop open and searched for Thorstad’s trademark six-foot-two frame. He wasn’t there.

But little Bashir was. His gaze immediately took in the one thing all kids zero in on. His face beamed when he saw the candy bag. He kicked his soccer ball over to me and stopped expectantly. Thorstad trained him well. “May I have some candy, sir?”

Gul was in his element, cutting a customer’s hair and chatting away.

He didn’t even know I was there. I felt as though I should at least ask his permission before doling out candy and ruining his kid’s appetite. I cleared my throat.

Gul glanced over, took in the scene, and began to scold Bashir.

“If it’s OK, I’d like to give him some candy.”

Gul studied me for a moment, and then his face broke out into a grin. Gul was known around camp for being very protective of his son. I wondered if I had made it into the inner circle yet. “Yes, yes, Mr. McCann. Candy is fine. Not too much, OK?”

“OK.” I dug around in the bag and pulled out three pops, grape, cherry, and chocolate.

Bashir held his breath.

He took the pops from me, breathed out a puff of air, and then smiled as if he’d just won the lottery. “Thank you, Mr. McCann.”

“Call me Mac,” I said.

“Thank you, Mr. Mac.” Bashir smiled, his eyes lit up. He unwrapped a pop and stuck it inside his mouth where it made a lopsided bulge.

I now knew why Thorstad was hooked. Just seeing Bashir happy from such a simple thing was as satisfying as any accomplishment I’d had that week. Bashir tugged at my heart, but there was something else. I didn’t want to admit it. I was jealous of Gul Hadi. I glanced at him again, as he made conversation with his customer. Though I had material things, he seemed at that moment to be a much richer man.

Bashir tugged at my sleeve. “Mr. Mac?”

I glanced at my watch. I needed to relieve Travis from dog sitting. Hopefully, I could save the rest of Sophie’s cinnamon rolls. “I have to get back to my tent, I have some things to take care of.”

Bashir’s face fell. He shifted the pop from one side of his mouth to the other.

He took my hand and determinedly pulled me toward the door, kicking his soccer ball ahead of him. He chattered excitedly in Dari to Gul.

I dug my heels in. “Whoa there. What are you up to?”

Bashir looked at me with pleading eyes. “I want to kick my soccer ball with you. The field is just this way. Please, sir.”

I was no soccer champ. Baseball was my sport, but Bashir’s sincerity shattered my objections.

Gul glanced over his shoulder and spoke sternly in Dari to Bashir, and then he turned to me. “It is up to you, Mr. McCann. If you wish, the soccer field is just across the patio. Please keep him away from the gravel path.” Worry creased his forehead for a moment. He was remembering the MRAP.

Bashir tugged again at my hand and pushed against the closed door, rattling it.

A deep sigh made its way up my sternum, but it was a sigh of release.

Bashir was so thrilled to have someone to play with that he galloped across the patio. When we reached the ground of the soccer field, he directed me with a wave of his hand. “You stand there, Mr. Mac, those two tires, my goal. I kick to you.”

“I defend this goal?” I pretended not to understand.

Bashir laughed with boyhood abandon. “Of course you defend the goal, the tires. Don’t you know how to play soccer?”

I hung my head in mock dismay. “No, Bashir. I’ve never played that sport in my life.”

He picked his ball up off the ground and trotted over to me, wonder spread over his face. “What do you play in America?”

I dug around in my backpack, found my wallet. Flipped the pictures out. Inside was a picture of me as a boy, about Bashir’s age. I was dressed in a blue striped, little league baseball uniform. “Laurel Little League” was stitched across the front. I showed the picture to Bashir. “This was me when I was your age. I played baseball.”

He rubbed the picture with his finger and pointed to a tall man with dark hair at my elbow. “Who is this man?”

“My dad. He was a coach.”

Bashir glanced at the mitt on my hand in the photograph. “What is this?” The boy was full of questions.

My heart tugged. I had so many advantages as a child. If only I could give those opportunities to Bashir. “A mitt, to catch the ball.”

His eyes glittered with mischief. “Here is my head, to bounce the ball.” He tossed the ball into the air and bounced it off the top of his noggin. It landed a few feet from us. He ran after it, and with a quick swipe of his foot rushed the ball between the makeshift goal. “You are not a good goalie.” He laughed.

I backed up, placed myself between Bashir and the goal, and tossed him the ball. “Try that again,” I yelled above the screech of a jet that raked the sky above camp.

He rushed the goal, shuffled the ball back and forth between his feet. With one last effort, he kicked the ball with all his might toward me, but I was ready. I smacked the ball back at him. It bounded in an arc and disappeared over his head.

He stopped in his tracks. “You are good soccer player, not bad.” He grinned at me.

I lost track of time. Sport worked its healing powers on a lonely little boy in a war zone and a man who’d lost his way. We played together until the sun rolled down behind the mountains that bordered Kandahar. “That’s enough for today. I need to get you back to your dad.”

He picked up his ball, tucked it under his arm, and we walked back to the barbershop together. For the first time in a while, I left my heart unguarded. Bashir managed to breach a place I was running from. I opened the door to the barbershop, and Gul was sweeping up.

“You walk us through the front gate?”

I glanced at my watch. I needed to get back and feed Phoenix, but I nodded my head.

Gul inspected the two of us. “Was he a good boy?”

“Champion. You’ve done well, Gul.”

“I beat him at soccer, Baba.” Bashir beamed.

“That is not polite, to brag what you have done. It is fine to win, but it is better to be silent.” Gul shook his head disapprovingly at Bashir.

“Hold my hand,” Bashir ordered and grabbed my fingers in his small hand.

Gul locked up shop, and we headed toward the front gate.

It felt good to hold Bashir’s hand protectively, to feel his footsteps fall in line with mine. I delivered the pair to the gate and watched as Gul’s strong back swayed next to Bashir’s tiny frame. They headed into the city to return to a culture I had no part of, to face dangers the average American couldn’t begin to comprehend.

~*~

“What’s that you’re reading?”

Travis stood in the middle of my room, a perplexed look on his face, a sheet of paper in his hands. I glanced over his shoulder at the article. It was a printout of an Internet page. “No Dog Gets Left Behind,” the banner read, and under it, a picture of a mixed-breed dog with a woebegone look on his face. I stashed the bag of pops in my gorilla box.

“I don’t know. I went to the latrine, and when I came back, this was shoved under your door.”

“I told you to stay and watch Phoenix.”

Travis held his hands in the air in exasperation.

He passed the page, and I read the article. Seemed the organization helped soldiers ship rescued dogs home to the states. Exactly what I needed. There were contact e-mails and a snail mail address. “I’ll get on this quick. They may be able to help get Phoenix home. Who do you think did it?”

Travis sat on the bed and rubbed his temples. “I don’t know. That’s what I was wondering when you came in the door. It has to be Glenn. We’re trying to hide him from everyone else.”

“Glenn never struck me as caring too much about Phoenix.”

“Glenn’s hard to read, but it’s still my best bet he did this. If you ask him about it though, he’ll deny it. He’s always going around here doing stuff for other people without them knowing.”

I sat down at my computer and zipped off an e-mail immediately to the head of the organization. “I had a close call with Colonel Smith, but it’s only a matter of time before my next visit to his office really is about the dog. Here. Read this, and tell me what you think.”

Travis studied the screen from his perch on the edge of my bed. He had Phoenix’s head cradled in his lap. “Yeah, I’d attach a photo, too.”

I inserted the saddest photo I could find of Phoenix. It was the day we rescued him. He was still covered in ashes.

“If they turn this down, they have wooden hearts.”

Travis scratched Phoenix’s neck. “You’re going home, boy.”

Travis’s proclamation gave me joy and sadness at the same time. Phoenix provided me comfort on late nights when explosions seemed too close, and when a seven-by-seven-foot room seemed as empty as the darkest cave. “I hope you’re right.”

I thought about sending Sophie a quick note to let her know her package arrived just fine. I could also let her know a little guy named Bashir loved those pops. Maybe she’d send more. I pulled my inbox back up. I already had a message from Sophie. “Travis, I’ve got an e-mail from Sophie I’d rather read alone. I’ll see you tomorrow at breakfast.”

“Oh, yeah, sure.” Travis scratched Phoenix’s ears one last time. “Let me know when you hear back from that organization.”

“I will.” I heard the door to my tent close. I was too focused on reading Sophie’s e-mail.

Mac,

It’s been pretty quiet around here since you’ve gone. I’ve had a lot of time to think. It’s been hard having both the men in my life gone. But something I read made me feel better. When I read it, I realized for the first time I have something in common with King David. We both lost sons, and we’ll both see them again.

I bet he’s up there right now, holding his son.

Below were lines she’d highlighted. Bible verses.

I hadn’t read the Bible since Vacation Bible School. I was eight. The room was stuffy, and the teacher seemed as though she’d rather be anywhere else than with a roomful of kids. She handed out verses on slips of paper we were supposed to memorize. The only thing I enjoyed was the felt board. When she left the room, I’d re-arrange the animals. Made the giraffe pilot Noah’s Ark. Noah swam behind.

Those weren’t little kid’s stories Sophie sent.

I wasn’t even sure I wanted to read it. I settled deeper into my chair and mouthed the words.

“David got up from the floor, washed his face, and combed his hair, put on a fresh change of clothes, then went into the sanctuary and worshiped. Then he came home and asked for something to eat. They set it before him, and he ate. His servants asked him, ‘What’s going on with you? While the child was alive, you fasted and wept and stayed up all night. Now that he’s dead, you get up and eat.

“‘While the child was alive,’ he said, ‘I fasted and wept, thinking God might have mercy on me and the child would live. But now that he’s dead why fast? Can I bring him back now? I can go to him, but he can’t come to me.’”

My chest tightened. Did she think that would make me feel better? I’d never see our son again. I hit delete.

13

“Tall mocha frappe.” I trudged over to the canopy-covered patio and slumped into an Adirondack chair. Classes were over, and the next day the academy would be closed. I was ready for a break.

Teaching was fun, seeing the guys learn new skills, cutting up with them between classes. But a threat hung over our heads of attack from outside or even being betrayed by one of our own students. An emotional drain.

How did Travis and Glenn do it year in and year out?

At least I could finish out my tour thanks to Colonel Smith. I was grateful for that. I needed caffeine. I made a Green Bean’s Coffee run and settled in at one of the tables.

A cup plunked down in front of my eyes. The uncharacteristically boyish face of Glenn Thurman grinned at me.

“What’s that sugary stuff you’re drinking, with that little frou-frou whipped cream on top?” His eyes crinkled, and he looked smug. A thin line of mustache was beginning to become more pronounced across his lip. He was entering Travis’s beard contest after all.

“Mocha frappe.”

“Coffee for infants.” Glenn threw his head back and chugged from his cup. “You need some real coffee.”

“And that would be?”

“Espresso, four shots. Makes you beat your chest and triumph over your enemies.” Glenn took another swig, and then set his cup down. He studied me. “I heard about your run-in with Stockton.” Surprisingly, his tone wasn’t accusing. He almost seemed saddened by my luck, or lack of.

I stirred the whipped cream into my coffee with the straw. Of all the topics he could choose, Glenn was a master at picking the one I most wanted to avoid, but his sudden hint of understanding made me lower my guard. “I’m still trying to decompress from that little altercation.” I reluctantly gave Glenn the information he wanted. “I can’t understand why Stockton feels the need to cause trouble. We could accomplish the same thing without the drama. I just want to be left alone to do my job, that’s all.”

“I told you to steer clear of him.” His brows bent down, and the old look of a principal shadowed his face again.

“I know, and I did, but he was like a bulldog. Wouldn’t give it a rest. I turned in my letter of resignation, but the colonel fixed things for me.”

“Stockton’s an odd bird, but the colonel’s a good man. I hear he even drinks espresso.” Glenn’s grin spread. “So, McCann, you’re officially one of us.” He studied me with renewed interest as if I were an organism, trapped under the lens of his microscope.

The old uneasiness returned. Would Glenn keep treating me like a greenhorn?

“Tell me about your hometown.”

I tapped my cup on the table to mix the ice, swirled the straw around. “Huntsville, Alabama.”

Glenn’s face puckered. Being from Savannah, I thought I’d have an ally in him, but Glenn liked to hide his southern roots from everyone.

“I know what you’re thinking,” I said. “Cotton farmers. I thought that too when my parents moved us down from Maryland. Even though I was young, I still thought of the South as backward.” A red-hot poker seared its way up my neck at the thought. I had been as judgmental as the people I now dealt with.

“What changed your perspective?” Glenn was actually leaning in, interest gleaming in his eyes.

“Huntsville was primarily known for agriculture, but then Redstone Arsenal opened its gates and welcomed some of the greatest rocket scientists on earth. Ever heard of Werner Von Braun?”

“Well.” Glenn scrunched up his forehead, thinking.

For once I had him at a loss for words. “He and his team developed the Saturn V rocket.” I prompted.

“Oh, yeah. I remember studying that in school. That was the one that took a man to the moon.”

“Yeah, and Huntsville was responsible for much of the technology. We’re full of engineers in that town. You can’t throw a rock without hitting one. That’s why when I landed in Afghanistan i

t was such a shock to find many of my students had trouble reading and writing.” I took a long sip. Most of my coffee was gone, and I was stuck with chunks of ice.

Glenn turned his head, surveying the camp. From where we sat we could see the sniper-fabric covered fence that surrounded the academy, Green Bean’s stand, Abdul’s Jewelry and Gemstone Shop, and the barbershop. Behind us, the mountains rose up like some giant animal on its haunches.

Glenn took another swig of his coffee then offered up his story. “When I got here, it was the farthest thing I’d ever encountered from home. I’m a history buff. Thought I knew about Afghanistan. What I thought I knew was actually romanticized history: Marco Polo and travel on the Silk Road, elementary school tales of treasure and adventure. What I found was a place destroyed from so many different occupations. Buildings were built, bombed, then abandoned. Schools are inadequate or nonexistent.” He turned and pointed past the rutted soccer field. “Over there is what’s left of the old fruit orchard. This used to be a cannery. It was productive. That cement pool behind us is where they washed and processed the fruit.”

“Didn’t know that.”

“If you go down the path that runs alongside the pool, there are rose bushes, miraculous things, growing in the middle of dust and death. The Afghan guards keep them up, trim them, and give them water when it gets too dry. It’s ironic.”

“Ironic?”

“In the middle of this struggle to survive, man’s spirit still craves beauty.”

I stabbed at the ice chunks in my cup, tried to break them up so I could get one last sip through the straw. I had no reply for Glenn. This was the first time he’d let down his guard enough to talk.

Glenn swirled his coffee cup. He drew a long drink then set the cup down. “I’m on my third tour here. Been stationed in J-bad and Kandahar. Everywhere it’s the same story. Not enough education available.”

I tried to suck down the last bit of coffee, but it was useless. I only ended up making an annoying slurping sound. When I glanced across the top of my cup, I noticed Gul Hadi and Bashir over at the next table.

Bashir darted back and forth, in perpetual motion. Now and then, he tilted his face up for a sip of his daddy’s drink. Bashir took a second from his wanderings, and his eyes lit up when he saw me.

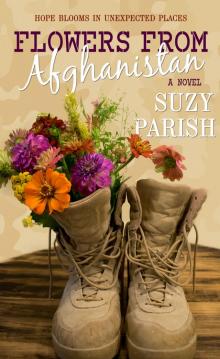

Flowers from Afghanistan

Flowers from Afghanistan